you thrift because you have commitment issues

Compulsive shopping, the Sociologist of Misery, and knowing exactly what you want

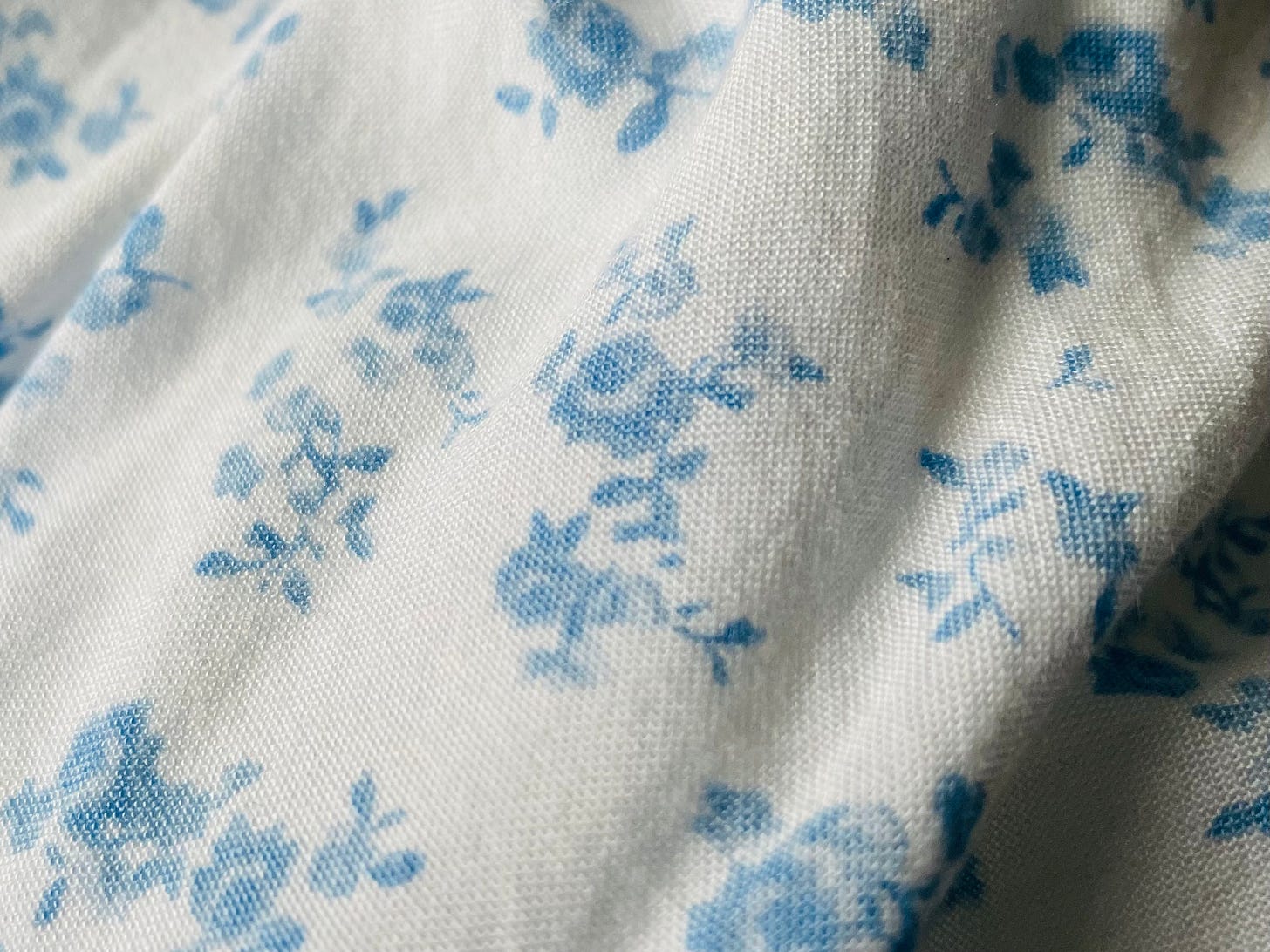

Anyone who has seen my closet already knows: I am obsessed with dresses.

And since I can’t walk past a row of dresses without falling in love with at least one of them, thrift stores are the oasis where I can safely quench my thirst for shirred waists and puffed sleeves.

I think to myself, a dress for only $8.99? What a deal!

But here’s the subsequent conversations I always have with myself:

“It’s not really my color.”

“But it still has the price tags on it! it would be foolish not to buy it. This is an investment.”

“Ah, I see. I’m saving money, actually.”

“Um, this isn’t my size.”

“But it’s so beautiful! Just wear it to events where you’re not going to be bending over, sitting down, or lifting your arms above your head.”

“Sounds like a plan!”

“I never wear backless dresses. This will just hang in my closet for months.”

“But it looks so good on you. Maybe just this once?”

“I guess it’s worth a try!”

It’s too big, too small, too mature, too childish, too warm, too cold, wrong color, wrong size, wrong fabric… But for only $10, I could make it work. Right? I’m never going to find a dress like this one ever again—will I regret passing up this opportunity?

The problem is that I go through this routine every single time I go to the thrift store, and a dozen ten-dollar-decisions later I have enough dresses to clothe an entire cottagecore village—yet nothing to wear.

Every few weeks I find myself still in my pajamas moments before I’m supposed to leave for some event, with dresses I don’t want to wear strewn over my desk and across my bed and slipping off hangers in the closet, and in moments like this I’m asking myself: wouldn’t it be cheaper to stop thrifting and wait until I find a dress that’s the right size, right color, right style—even if I have to pay full price? Wouldn’t I be happier, and save money, if I only bought clothes I really really loved? Wouldn’t I rather have one perfect dress than a dozen I never wear?

Thrifting has become a mainstream activity, and I know I’m not the only one like this. For many of us, thrifting isn’t just a cheaper and more sustainable alternative to clothes we would have paid full price for—it’s a guilt-free way to expand our wardrobes with items we won’t wear, gamble $4 that maybe we do like sweater vests, and make decisions we know we’ll regret because the consequences are so low. Later we find ourselves surrounded by choices we settled for and wondering if, in the end, chasing temporary satisfaction has cost us more than the desires we thought were too expensive to be worth fulfilling.

Zygmant Bauman, Polish–British intellectual known as the “sociologist of misery,” refers to this as contingency.1

Bauman was a strong critic of Postmodernism, a philosophy that took root in western culture in the second half of the 20th century. Postmodernism holds that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of representing reality; traditions and organizations are biased power systems that oppress us into inauthentic lives—so we should live completely free from any kind of imposed structure.

But Bauman considers postmodernism the full untying of our identities. In an unstructured society, we have so much freedom that none of our decisions mean anything. If our choices cost us nothing and we can revoke them as soon as the consequences become uncomfortable, then they have no lasting impact on us—or anyone else. You’re free to abandon your career, leave your spouse, change religions, move across the country, and become a completely new person. But if the choices you made yesterday have no binding on you, do the choices you make today even matter? If the past has no hold on the present, the present has no hold on the future. If all of our decisions are meaningless, we don’t actually live in freedom, we live in contingency: “a state of perpetual new beginning and fresh start.”

Bauman describes life in the age of contingency as “a city in which traffic is daily rerouted and street names are liable to be changed without notice.” There’s no guarantee that your destination will still exist by the time you get there. So a wise person avoids long journeys and doesn’t commit to anything. Costly choices just don’t make sense. Why go to school for a job that might not even exist when you’re thirty? Why invest in an industry that could collapse tomorrow? Why make friendships in a city you’re only living in for a few years? Why love someone who could someday leave you? Saving up for a big dream is too risky. It’s better to be half-satisfied now than take your chances and be disappointed later. It’s better to buy five ten-dollar dresses I don’t love than wait around for a fifty dollar dress I truly adore.

In 1930, the average American woman owned nine outfits and bought five new pieces a year. Today, she buys more than sixty new articles of clothing a year.2 We buy five times as much clothing now as we did in 1980. There used to be four Fashion Seasons; now there are 52 “micro-seasons,” constantly giving us new trends to keep up with, new designs to fall in love with, new desires to fulfill. This is the clothing culture we live in.

So people say thrifting is affordable, it’s sustainable… Sure. Whatever.

I think thrifting is actually just another product of our consumerist, contingent culture. It enables our materialism without challenging our commitment issues. Thrifting doesn’t confront our obsession with more, new, bigger, better—it’s just a low-cost alternative to feeding our addictions. I have a friend who thrifts so many pairs of white sneakers that she had to donate some back to the thrift store—but now she just lives in fear of accidentally buying back her own shoes. We’re still women who love buying things we don’t need, thrifting just makes our problem an affordable one.

I could write an entire article (if not a book?) on the ethical and environmental consequences of Fast Fashion. But the volume of our consumption—regardless of where it comes from and who was hurt in the process—is symptomatic of a separate problem: we don’t commit to what we really want. We’re a generation with huge, beautiful dreams. Dreams that would cost us everything we have and more. But we believe that the world is so unstable and unpredictable, it’s better to squeeze ourselves into hand-me-down destinies and roll up the sleeves on second-hand-realities and lie to ourselves that someday we’ll hem our clearance-rack lives. We’re afraid to commit to the loves or careers or communities that our souls long for.

And of course, clothes are just clothes. My life isn’t cheapened if I’m not buried in a Reformation dresses and Prada sunglasses and real cowboy boots. But what I have learned from clothes is that I always knew exactly what I really wanted. I wanted that black dress from Urban Outfitters. I wanted that white dress from Hollister. I wanted Lululemon leggings. I spent years telling myself I couldn’t justify spending $50 or $100 on those desires—but eventually I did make those expensive commitments, and realized that they had been worth it all along. And I realized that I’d spent far more money trying to find cheaper ways of filling the void in my closet for slinky black dresses that fit just right and fluttery dresses that look like spring and leggings more comfortable than my own skin. My only regret is that I spent so long believing my dreams were too costly to be worth the commitment.

I’ve worn the same Old Navy running shorts almost everyday for years. But deep down, I want Versace and elegant pajamas and a rook piercing. Similarly, no matter what my life might look like, I wouldn’t be able to deny the future I really long for: I want to write a book. I want to get married. I want to join the 500 Club. I want to do a marathon swim race. I want to be a mayor, a doula, and a journalist. I want to ride horses at sunset.

And I think that, deep down, you know exactly what you really want too. You want to go back to school, start painting, ask that girl out, get a tattoo, reconcile with your dad, throw away all the stuff in your attic. No matter how long you’ve tried to smother your risky and exhilarating dreams, we’re all haunted by hopes so wild that we hide them from ourselves, assuming it’s best to just settle somewhere on the journey towards what we really want. We’re willing to lead lives of cheap fabric, itchy sleeves, and stains we hope no one will notice.

But I believe that every human being is designer, and it’s time to stop living like we bought our lives on clearance. You don’t have to fulfill every desire to lead a life worth living—but life is precious enough to deserve our bravery and intentionality.

Bauman said the contingent life is like a city where the roads are continually re-routed, but I see so many people stuck in traffic. People are sitting through jobs they hate, relationships they’re only tolerating, degrees they don’t even want. In the end life is long and time-consuming and expensive no matter how free you try to be—and even if the modern world is unpredictable, we’re going to be traveling through life for long enough we should find a destination that’s worth the drive. We can live for a hope that’s worth the journey.

In Morality in The Age of Contingency, https://yale.instructure.com/courses/83362/files/folder/week%203%20articles?preview=7224895

From Overdressed, by Elizabeth Cline.