Every once in a while you walk past the house you grew up in. This is the house you loved. The house where you were loved. The house where you learned how to love.

But that was years ago.

Now, the sidewalk beneath your feet is cracked like the shattered beer bottles on the side of the highway and the porch sags downwards, like a man falling asleep on the bus. The old pine tree in the front yard is overgrown and its shaggy branches cover the shutterless windows in shadows. Moss has crept across a roof that should’ve been replaced years ago, and the whole house just looks damp.

But it’s not your home anymore and you don’t know any of these new neighbors. You can’t stand here for too long.

You keep walking.

After your family lost the house you bounced around, staying with friends or relatives, sleeping on couches and sharing beds until your parents found an apartment in the next town over. You’re an adult now, you have a place of your own, but you still believe that this house should have always been yours. You should have parked your first car in this driveway and brought your first love through those doors. You should have learned how to mow this lawn. You should have woken up to the smell of bacon frying in that kitchen on Saturdays.

In the Old Testament, after the Israelites leave Egypt, they wander in the desert for forty years. And while they’re wandering in the desert, before entering the Promised Land, God gives Moses some laws for how God wants his people to live. Today, as Christians, we believe we don’t have to follow these laws—but they still show us something about God’s character.

Maybe you’re familiar with the Sabbath—one day of rest every seven days. But the book of Leviticus introduces this concept of a sabbath year—every seven years, let the land rest. But then there’s a sabbath of sabbath years—a mega ultra sabbath that happens every seven times seven, or every 49 years. And that 50th year is called the year of Jubilee.

Leviticus 25:8-13 gives further instructions:

“Then [during the year of Jubilee] have the trumpet sounded everywhere on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the Day of Atonement sound the trumpet throughout your land. Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan. The fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; do not sow and do not reap what grows of itself or harvest the untended vines. For it is a jubilee and is to be holy for you; eat only what is taken directly from the fields. In this Year of Jubilee everyone is to return to their own property.”

So on this Day of Atonement, there’s liberty throughout the land. Debts are cleared, servants1 are released, everyone returns to their property. The assumption behind the year of Jubilee is that people have to give things up during difficult times—you’ll have to sell your farm, give up your freedom, and take on debt. You’ll be forced to give up your family’s property and work someone else’s land. In an agricultural society like this one, losing your family’s land might be compared to spending years of your life and investing all your family’s resources into becoming a doctor, planning to open your own practice, but then losing your job and having to work at a fast food restaurant instead. Not that there’s anything wrong with frying chicken nuggets or making lattes—but you’re supporting someone else’s dream, not your own.

But the Year of Jubilee means that even if you’re forced to give up your land, you’re only selling the property for—at most—49 years. During the year of Jubilee, the original owner’s family would be allowed to retake possession of the land. This isn’t some socialist thing. Property like cattle and money weren’t redistributed. There was still ownership of the land. But because every fifty years servants would be liberated, debts would be canceled, and families could return to their land, Israel would never have a permanent underclass. Poverty would never be the end of the story.

In the US, however, disadvantage and exploitation compounds with generations. Whenever I think about the Year of Jubilee, the first thing that comes to my mind is how much of a contrast that culture is with ours, where the legacy of enslavement and the following centuries of segregation, discrimination, and injustice have produced a racial wealth gap where the typical white household had 9.2 times as much wealth as the typical Black household– $250,400 vs. $27,100—in 2021. 2

And regardless of race, in our country the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. A 2020 study from the Pew Research Center found that upper-income families were 7.4 times wealthier than middle income families and 75 times wealthier than the lower-income families; in 1983, these ratios were 3.4 and 28.3 Pew explains that one reason the wealth gap widened is because home equity is a primary source of wealth for middle-income families—meaning that their house is usually their most valuable asset—so they were devastated when the housing bubble burst in 2006. Upper-income families, however, often attain wealth through financial market assets and business equity, so they were able to recover from the recession more easily.

But imagine if, every 50 years, the families who profited off of other people’s losses had to restore their homes. Imagine if the families who benefited from exploitation had to return that wealth to the people on whose backs it was gathered. The Year of Jubilee would totally change people’s outlook on the other 49 years—if you knew you would eventually return to whatever assets your grandparents had the same way we’ll eventually return to the earth as empty-handed as we were born, it wouldn’t make sense to exploit other people in the first place.

But social justice isn’t the point of the year of Jubilee. In verse 23, God explains why he commands a return to the land during the year of Jubilee: “The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine. For you are strangers and sojourners with me.” The land isn’t really ours, so we can’t sell it forever. God gave it to the people he gave it to. And Jubilee means that no family will forever be without land.

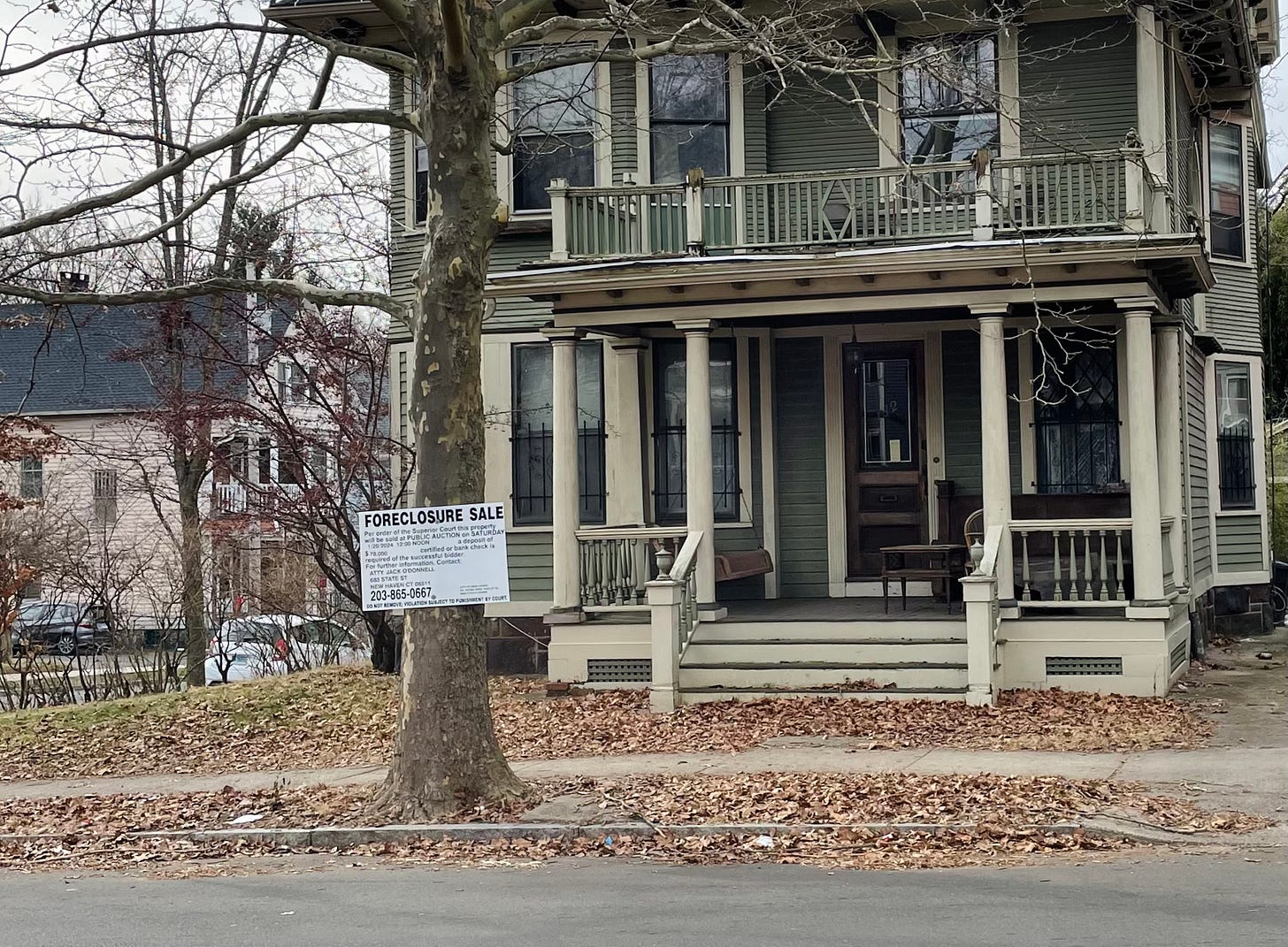

Meanwhile, In the US, you can “buy” land but your family has no certainty that they’ll always be able to return to it. You’ll likely be paying the mortgage for decades, and you’ll be paying property tax forever. If you can’t do this, you can lose your house—and once you lose your house it’s hard to recover. Going into foreclosure will drop your credit score, which is how banks decide whether to loan you money. It’ll be harder for you to get a new loan at a good interest rate, meaning you’ll be paying more to borrow money. And your credit score is also one way employers and landlords assess your reliability, so a lower credit score can make it harder to get a job or find a new place to stay.4

Should you find yourself without a home at all, the median length of literal homelessness is only 2.6 months. But we all know that once you’re homeless, it’s harder to get and keep the employment necessary to afford housing. And even after a person is no longer “unhoused,” it can take far longer to escape housing insecurity, to actually have a stable home. A recent study of 60,000 homeless people in Boston found that their average age of death was 53.7, decades earlier than the nation’s 2017 life expectancy of 78.8 years. So in the US, losing housing can actually cost you a third of your life.5

But the year of Jubilee was never intended for modern Americans. This law really only makes sense in an agricultural economy with slow population growth, and a situation where God has literally given the land to specific families. Even in the Israelite context, there’s no evidence that the year of Jubilee was ever actually widely observed. But what I want to point out here is that this is God’s preferred way of handling situations where there is poverty, there is misfortune, there is famine, and people had to sell their land and their freedom to get by. The year of Jubilee shows us that God doesn’t intend for anyone to be trapped forever.

So in the US, in our culture, we’re used to homelessness being inescapable, incarceration being inescapable, debt being inescapable. Your sins and losses will be a mark against you forever. This is just how we think. But God doesn’t roll like that. And that matters because humanity did lose the family farm. When Adam and Eve sinned, we lost our home. There’s a big FORECLOSURE sign in front of the Garden of Eden.

But Christ brings us back.

The Day of Atonement, the day that begins the Year of Jubilee, was an annual event. On that day, only the priest could enter the most holy place, where he made atonement for Israel’s sins. The Day of Atonement cleanses, re-establishes, and resets Israel. And that’s why it’s also the day that debts are cleared and servants can go free.

But the Day of Atonement is symbolic of and anticipatory of Christ. When Jesus begins his ministry in Luke 4, he reads from Isaiah 61, announcing “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives… to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And Hebrews chapter 9 explains that with Jesus’s death on the cross and his resurrection, he was the high priest who made atonement for our sins. Christ means that we’re living in the year of Jubilee.

So in our culture, when we’re in moral, spiritual debt, our baseline assumption is that we’ll either work really, really hard to pay it back—or we believe that we’re so far gone, we’ve sinned so much, we have no shot at ever “making it up” to God. But Leviticus shows us that we need to challenge that assumption. With God there are consequences to our actions, yes, but every day is a Day of Atonement. Jesus reset the economy of your heart. What he does for your soul is the same thing that the Year of Jubilee does for land—he’s paid your debt and set you free.

“Maybe we can powerwash this,” Jesus says, pointing to the moss on the concrete steps with the toe of his shoe.

You’re standing on the front porch of the house that’s always been your home and Jesus rips all the warnings and notices off the front door. He paid the full asking price for the house, in cash. No mortgage. It’s fully his—and therefore yours again too.

You know from the Zillow listing that the house will be completely empty inside. No furniture, just cobwebs. That overgrown pine tree will block the sunlight from coming through the blind-less windows of the North-facing living room, but Jesus says his Dad can prune it with a pair of hedge trimmers. Yesterday Jesus told you he wants to tear down the wall between the kitchen and living room, actually, so the light can shine all the way through to the back deck. You’re a little apprehensive because you don’t really want to change, you’re kind of attached to how dark and compartmentalized it is in there. But more than that you just want him to make this house his own, because you’ve seen that nothing is more beautiful than anything that belongs to him.

Jesus is holding the keys, he’s unlocking the front door, and you’re just standing there, jittery, suddenly nervous to be coming back home. To have a place that’s stable and safe again.

Jesus opens the door, steps over the threshold, looks back at you with a smile.

All you have to do is follow.

A note about the servitude we’re discussing here—a poor Israelite could “sell” themselves during hard times, but laws (like the Year of Jubilee) prevented this from becoming the horrific form of human slavery that Americans might imagine. Israelites weren’t “buying” a human being, they were renting a brother’s labor for (at most) 49 years. It was clear that a person’s life belonged to God alone.

From “Wealth gaps across racial and ethnic groups.” Wealth is defined as the value of assets owned by every member of the household, minus their debt.

From “Foreclosure Consequences.”

From “Why it’s so hard to end homelessness in America” by the Harvard Gazette. Obviously there’s a LOT more going on here that causes those numbers. This is more of a causation than correlation statistic, but my point is that being without a home puts you in a very vulnerable position.