I think that we tend to organize our land in the way that just makes sense. We raise cattle in places where cattle do well. We plant orchards in places where orchards do well. We build cities in places where cities do well. We (generally) use land in the ways that will be most successful—so after reading The Hunger Games, I find myself with some contrarian suggestions about where Panem’s twelve districts should actually be, based on land use today.

(please debate me on any of this, it’s all speculation anyway)

District 1, 2, and 3 could be anywhere because their industries (luxury items, masonry and weapons manufacturing, and electronics, respectively) are a step removed from the raw materials. We just know they have to be near the Capitol, which is supposed to be somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. The only issue with this is that those raw materials (gold, iron, lithium, etc.) have to come from somewhere. And it seems like Panem only mines for… coal. Districts 1, 2, and 3 are implausible without District 12-ish labor to provide those natural resources.

This is also my problem with the “transportation district,” District 6. First of all, I think this is kind of stupid because “transportation” isn’t a place. But I could imagine District 6 as an industrial city that assembles trains and cars. Maybe it’s a future version of a Rust Belt city, like Chicago or Detroit or Pittsburgh? Cars are never mentioned (at least, not in the books?) but Panem is heavily dependent on trains, so they would need a place to support the railroads that run from District 12 to the Capitol to everywhere in between.

But, if we pretend that a transportation district makes sense, the next question is—where does the iron and steel come from? Is it all recycled? Imported? There’s nothing left to rust in Panem’s Rust Belt cities.

It’s easier to map District 4. The fishing district obviously has to be coastal. Its proximity to the Capitol (and its population of sexy beachy people?) imply that District 4 is analogous to California—but that’s not necessarily true. The 2020 Fisheries of the United States Report indicates that, actually, states bordering the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico had higher volume and value of seafood than the Pacific region. District 4 would more likely be a place like Louisiana or Alaska rather than California. Florida would be a good candidate too, but NOAA predicts that it just won’t exist after sea levels rise that much.1

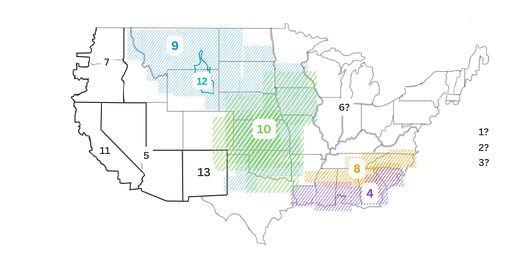

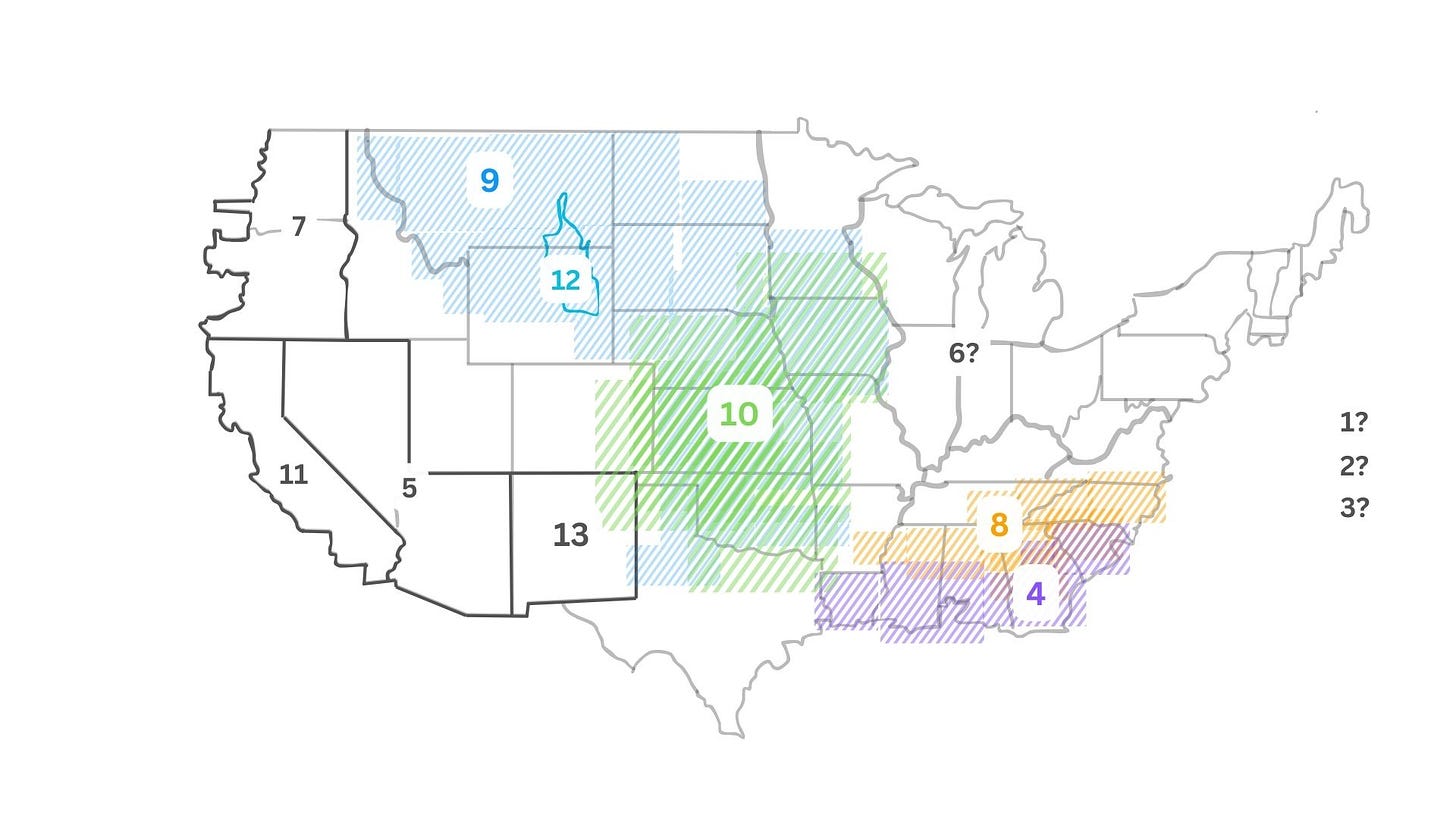

Actually, California is a good candidate for District 11. While District 11 is described as being just below District 12 (which Collins defines as approximately West Virginia) and is very much South-coded, it’s not the agricultural center of the United States anymore. In 2017, the Value of Fruits, Tree Nuts, and Berries Sold as Percent of Total Market Value was concentrated in California. Vegetables are actually the highest percentage of farmland in California and New England.2

So while the American South isn’t District 11, it might be a good candidate for District 8. Personally, the idea of a textile district evokes images of the Industrial Revolution—women at mills in Massachusetts, or turn-of-the-century immigrant child laborers on factory floors in New York City. But because the American South grows so much cotton, North Carolina has actually been the center of the American textile industry since World War I.

Since Panem’s textile industry isn't necessarily dependent on water-powered mills (which it was during the industrial revolution) it could be anywhere—but close to cotton would be logical. So I predict that either District 8 would be in the South, and have labor that looks more like how Collins imagines District 11—or that District 11 would harvest cotton and District 8 would be very close to it.

Speaking of the South: it would make sense for District 7, the lumber district, to be in the pacific northwest. But actually, since the 1950s, the US has increasingly gotten its lumber from the southeastern states. Without the timber management plans and public forests that have caused that shift, however, I imagine that Panem would once again source most of its wood from the National Forests. District 7 would be centered in Washington, Oregon, and northern California—those beautiful places where the trees are older and more majestic than the people who cut them down.

And District 5, the electricity district, would (I guess?) be Arizona/Nevada. The hydroelectric dam is giving Hoover. And the Southwest, with its solar farms and turbines, just makes sense.

This leaves us with Districts 9, 10, 12, and 13.

Based on the USDA’s Cattle and Calves Inventory from 2017, District 10—the livestock district—could reasonably be in northern Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska.

The only problem is, that’s already District 9.

According to the Grains and Legumes Nutrition Council, there are seven types of grains, including wheat, oats, rice, corn, barley, sorghum, rye, and millet. Each of these are centered in slightly different regions, meaning that the “grain district,” District 9 is…. huge. North Texas, Kansas, and parts of the Dakotas and Montana seem to have the most “Acres of All Wheat Harvested for Grain as Percent of Harvested Cropland Acreage.” But corn, specifically, dominates Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinios. Oats are concentrated in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and northern Maine; rice, in Arkansas and Louisiana and Texas along the gulf of Mexico. Sorghum comes from Kansas and Texas, but we wouldn’t have barley without Idaho, Wyoming, Montana.

I assume that Suzanne Collins imagined District 9 somewhere in the Great Plains states, in those landscapes we think of when we hear the lyric amber waves of grain. But that would mean that (barring climate change significantly altering where certain crops can grow) Panem is a society without very little oats or rice. (Which are clearly the best types of grain?)

But then there’s District 12, the coal mining district. The smallest and poorest place in Panem. Of course, a West Virginia-ish chunk of Appalacha is the first thing that comes to mind. At least, Suzanne Collins thinks so. But the Powder River Basin3 (Wyoming etc.) produces far more coal. If Panem actually needed coal, there’s no reason that they would mine here. The only justifiable reason for District 12 to be located here is to be a buffer between District 13 and the rest of the nation.

And District 13 is what really perplexes me. We’ve always concentrated weapons of mass destruction on the West Coast. Wikipedia says that “the U.S. Air Force currently operates 400 Minuteman III ICBMs, located primarily in the northern Rocky Mountain states and the Dakotas.” More nuclear laboratories and test sites are in New Mexico and Nevada than anywhere else. Those pictures of blooming mushroom clouds from the testing of nuclear weapons during the Manhattan project? That’s in New Mexico.

According to the books, the Capitol is located in the Rocky Mountains and built its own nuclear weapons after losing District 13. But if Panem inherited the land of the United States, why would they initially concentrate their nuclear weapons… in the place that has the most developed urban infrastructure, and not the places where it’s always made sense to keep weapons of mass destruction?

What would really make sense is to flip our stereotypical map of Panem: District 12 and 13 are in the northern Rockies, District 11 is California and District 4 is Florida, and the capitol is somewhere in the BosWash corridor.

Perhaps the shocking thing about this analysis is that we can recognize districts, and when we compare them to our reality we say “yes, but not there.” Obviously our economy is way more complex than the single-industry regions of Panem. Districts 4 and 8 and 7 and 11 are all entangled along both coasts, and Districts 6 and 8 are the nodes somewhere between. Districts 9 and 10 flow into each other across the middle of the country. And maybe it’s a sign of freedom that regions aren’t dependent on a single resource for survival— but even if we’re more diversified than Panem, we are separated into different realities based on our natural environment.

But why would the Capitol be in the Rocky Mountains anyway? Las Vegas is proof that you can build cities in the desert—huge, ridiculous, opulent cities full of debauchery and overflowing with nonsense. But I imagine that in the environmental conditions that Suzanne Collins anticipates, a city as unsustainable as Vegas would be even harder to achieve than it is today.

What’s the economic or military advantage that justifies building a nation’s headquarters in the Rockies? A city surrounded by mountains would be easier to defend and harder to attack, sure, but it would also be inconvenient to import things. The Capitol only makes sense if Panem has zero trade with Europe or Asia. It’s at the heart of Panem, it’s the central location that can demand resources from all the districts—but the Capitol has no engagement with a world beyond Panem.

Come to think of it—we never hear Capitol residents (who, surely, would be obsessed with exotic goods and global travel) talking about other countries. We never hear about people from District 10 sneaking into Mexico, or people from District 7 fleeing to Canada. Maybe this could all be explained by some sort of global Cold War or an American DMZ, but the Capitol’s only enemy is District 13. Basically, It seems as though Panem is just the only inhabited country in the world.

I read the first book in the Hunger Games trilogy over winter break, because my sisters wanted to see Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes and I didn’t want to spend money on a movie I wouldn’t even understand. And in my head, I pronounced Panem as the Latin word for bread—soft a, soft e: pah nem.

It wasn’t until we were in the theater watching Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes and Coriolanus said his nation’s name that I realized every other native English speaker pronounced Panem pan um. Pan Am. Pan America.

But as I was reading The Hunger Games, I didn’t recognize myself in the pressures and privations of District 9 or 10 or off the shore of District 12, the places where I grew up—instead, I recognized myself in the luxury of the Capitol.

The United States exports $1.63 trillion dollars of merchandise but we import $2.73 trillion—more than any other nation in the world. We spent $593 million dollars to film the Hunger Games franchise. We spent another $3.3 billion—which is almost the GDP of Liberia—to watch it. We have Botox and Ozempic and Dancing With The Stars. When I was in high school, we went to quiz bowl nationals in the Atlanta hotel where they filmed Joanna’s elevator scene in Catching Fire.

So I don’t think that the US is Panem: I think we’re the Capitol.

Obviously, real life is far more complicated than a fable. It’s impossible to divide the world into single-resource regions like the districts in Panem because that’s just not a viable way to meet human needs. I think that places are stratified into economic networks rather than districts. The Capitol is actually a web that includes Dubai and Luxembourg and New York City, and that the grease and grime of all the other districts simultaneously exist beneath the luster of these places. We wouldn’t have metropolises if we didn’t also have coal mines and landfills and slaughterhouses.

On a global scale, we can identify areas that source the precious metals, the seafood, the electricity, the transportation, the wood products, the textiles, the livestock, the vegetable products, and so on and so forth.4 Again, these aren’t neatly stratified into districts, they’re really more like overlapping networks—but if there’s a single place that collects the resources from all these other places, it’s us.

This is why Suzanne Collins can propose Districts 1 and 2 and 3 and 6 without answering the question of where raw materials come from, and so many of us unquestioningly accept that. We’re familiar with having iPhones and Toyotas and Owalas and Tupperware—and sometimes we still remember that these things get made somewhere—but few of us consider where our lithium and steel and plastic come from.

I think of this bit from the Communist Manifesto,5 where Marx says that as the bourgeoisie exploits world markets, existing industries “are dislodged by new industries… that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes.”6 In short, our desires and our manufacturing and our materials are now scattered across the globe. Rather than a single community starting with raw materials, producing a good, and then enjoying that product, we’ve separated each step in that process throughout the world—and now we don’t even know where our stuff comes from. We’ve forgotten that everything we hold in our hands always has and always will be on this planet. Our plastic water bottles and our granola bar wrappers go somewhere and they also come from somewhere. There are people behind our sweaters and sneakers and strawberries. How often do we forget these people and places the same way the Capitol forgets the districts?

Just some food for thought.

“Vegetables, Harvested Acres, as Percent of Harvested Cropland Acreage: 2017” from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/Ag_Census_Web_Maps/index.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_mining_in_the_United_States#/media/File:U.S._annual_coal_production_by_basin,_2014-2018_(31930259427).png

I would really really love a map that breaks this down by percentage of each country’s total exports because the problem with Panem isn’t that certain industries depend on certain places—it’s that vulnerability and inequality result when certain communities become completely reliant on a single industry.

I’m actually really curious about how Communism, both practical and theoretical, are present in the Hunger Games. I can tell that it’s a huge theme but I’m personally not well-versed enough in political philosophy to develop a reading that I’m satisfied with.