A friend recently pointed out that no one names their daughter Rahab. Which is a shame, because she’s one of the most awesome women in the Bible. The book of Joshua explains that Rahab was a woman from Canaan: the pagan nation that God promised would be conquered by his people, the Israelites. But when two Israelite spies come across her house as they’re searching out the land, Rahab offers them a hiding place on her roof because she has faith in Israel’s God. She believes that “the Lord your God, he is God in the heavens above and on the earth beneath.” (Joshua 2:11) Rahab has so much certainty in God that she’s willing to help the Israelites conquer her city and thus gain a foothold in the Promised Land. She’s later counted among the faithful Old Testament heroes—putting her name alongside figures like Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Gideon, David, and Samuel. (Hebrews 11:31)

But she was a prostitute, and her name hasn’t been in the top thousand most popular American names even once since 1900.

There are Biblical women we do and don’t name our daughters after. Names fluctuate in popularity—for example, Hannah wasn’t an especially popular name (it was ranked #884 in 1961) until it peaked at #2 in 2000. Meanwhile, 2.296% of baby girls born in 1961 were named Mary—which was the #1 most popular name for sixty years in a row—but Mary has steadily fallen to #136. One out of every fifty women born in 1955 was named Deborah, and we associate the name with baby boomers so much that it’s fallen to the 918th most popular name for girls born in 2022.1

I think our culture has largely forgotten the stories behind these names. I think most parents who name their daughters Rachel or Anna are thinking about Rachel Ray and Princess Anna of Arrendelle before they’re thinking of matriarchs and prophetesses. But these names entered our broader, secular cultural imagination at a time when people did know these stories. My guess is that at one point enough people did know the stories of Rachel and Anna to make these the kinds of names people give their daughters, and now even an increasingly non-Christian society follows their example without thinking. The same way that many people swear on Bibles and get married in churches regardless of what they believe.

But names like Rahab never entered our public consciousness, were never normalized like Rebekah and Ruth.

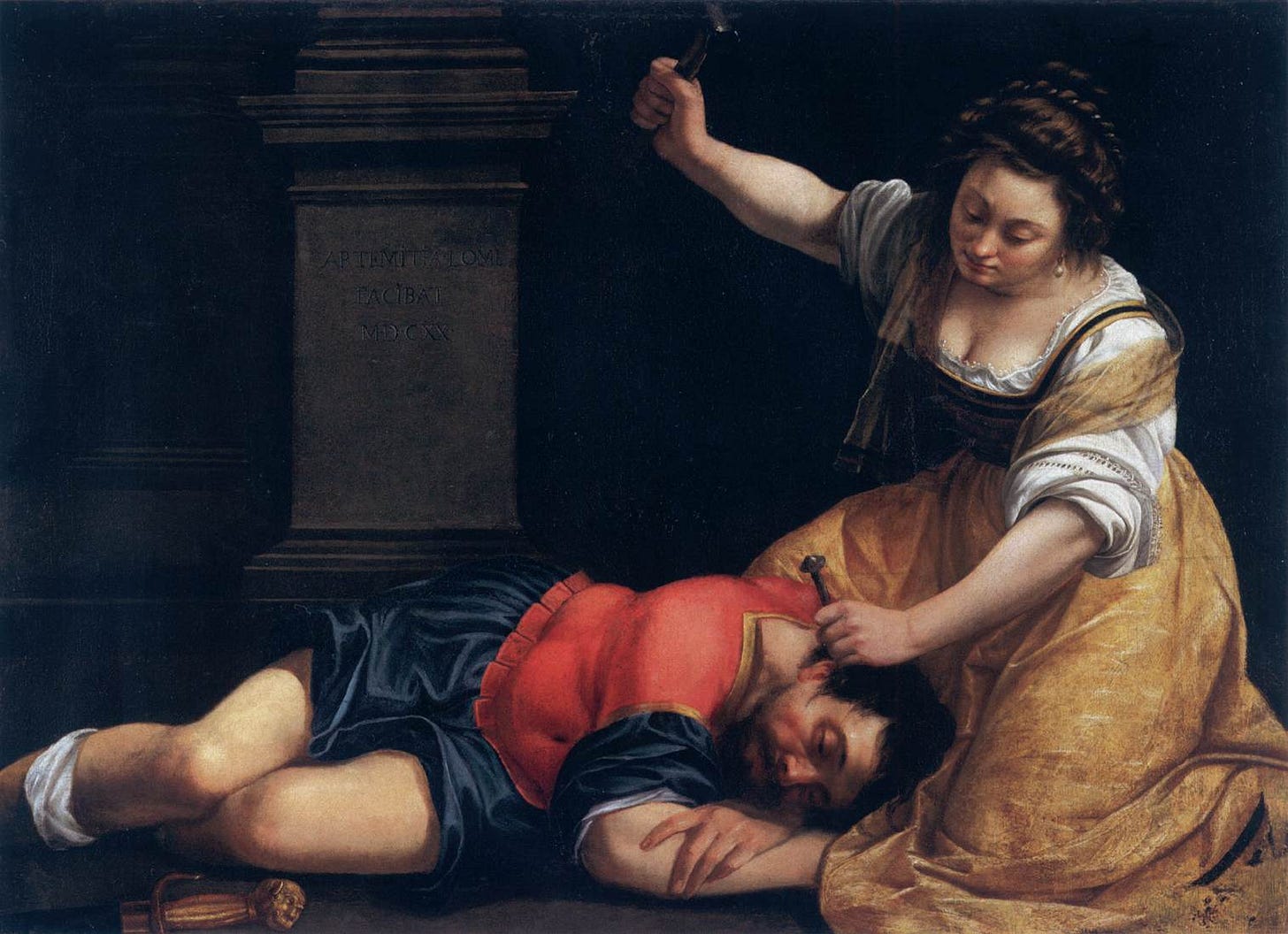

Jael is another woman we don’t name our daughters after. Like Rahab, Jael wasn’t an Israelite. The book of Judges explains that her husband was allied with a man named Sisera, the general of a Canaanite army waging war against Israel. So when Sisera is fleeing from a battle he rushes to Jael’s tent seeking a drink and a place to rest. She welcomes him in, and when he falls asleep she murders him—her husband’s ally, but Israel’s enemy—with one of her tent pegs, and promptly alerts the Israelites who were hunting him down. But we want to name our little girls after mothers not murderers, so Jael’s name has never been in the top thousand either.

Or consider Eve, mother of humanity. She did succumb to the devil’s temptation, and that’s what we remember her for. But that happened after she had lived in paradise and walked with God. I recently read a quote explaining that Eden is essentially described as a temple—and thus Eve is a priestess. More than Moses or Aaron or any of the men descended from her, Eve spent her life in the presence of God himself. And yet Eve was most popular as a baby name in 1907, when a whopping 73 girls were named after her.2

Of course, I don’t think we should name our daughters after every interesting Biblical woman. Take Tamar, for example. Her father-in-law, Judah, repeatedly cheats her of the opportunity to bear his heir, so she disguises herself as a prostitute and sleeps with him in exchange for his staff, cord, and signet ring. Three months later, when Judah is informed that Tamar is “pregnant by immorality,” she sends his belongings back to him. “By the man to whom these belong, I am pregnant,” she says. “Please identify whose these are.” Judah relents from punishing her, realizing “she is more righteous than I.”

So Tamar is brave and assertive. She seeks justice. Her son Perez is later recorded as an ancestor of Jesus. But—no one wants to burden a little girl with her legacy. We don’t name our daughters after women like Tamar because even if they are admirable characters and ancestors of Jesus, even if they are the people God uses to redeem the world—their stories hinge on rape, incest, prostitution, deception, temptation, murder, or just general weirdness.

I highlight the significance of these women not to recommend them as baby names, but to point out that God’s story uses women with lives we wouldn’t wish on our little girls. God’s plan prevails through events we don’t want to talk about in Sunday School. The Bible isn’t saying that these women’s stories are good (or even okay), but that this is the kind of stuff that happens in our weird, broken world and it doesn’t stop God from saving us.

And even the women we do name our daughters after—the women a traditional culture did approve of—are imperfect. Sarah isn’t exactly a role model. She lies about being her husband’s sister—twice. At age 90, she’s barren, and laughs at God’s promise that she’ll have a son—and then she lies about laughing. She still doubts that God can actually do what he says he’ll do, so she encourages her husband to impregnate her servant, Hagar—because maybe they can have a child that way. But when God does fulfill his promise and give her a son, Hagar’s son mocks her and Sarah is so bothered that she asks Abraham to send Hagar and her son off into the wilderness. So maybe Sarah is the mother of God’s people, maybe she is a woman of faith—but at times she is cruel, skeptical, and deceitful just like the rest of us. And yet her name has almost always been in the top 100 most popular names.3

We name girls after Rebekah, who married Sarah’s son Isaac, making her another major figure in the Isrealite family tree. But she facilitated her favorite son tricking her husband to steal his brother’s blessing—trying to steal the same blessing that Sarah thought she could unlock using Hagar as a loophole.

Or Miriam. As a child she watched from the riverside, protecting her little brother Moses as he floated in the reeds, and spoke up so that Pharaoh's daughter would send baby Moses back to his own mother. She grew up to become a prophetess, a leader like her brothers Moses and Aaron, standing beside the water again but this time leading women in a victory song praising the God who led them out of Egypt and across the Red Sea. But later on she questions Moses’s authority, speaking against him and against God. She’s temporarily covered with a condition like leprosy, and dies without seeing the promised land.

We name children after Queen Esther, who was beautiful and did eventually advocate for her fellow Israelites during exile in Persia—but her first reaction to danger was helplessness. She’s conflict-avoidant and procrastinates the hard conversation that would save her people. And God isn’t even mentioned in her story.

Delilah betrayed her husband, Samson, telling his enemies his single weakness—so I have no clue why her name has always been in the top thousand, even rising to 58th most popular in 2022.

Some Biblical women are genuinely faithful, honest people. But Hannah agonized in the shame of her barrenness. Mary faced the potential embarrassment of an unexplainable pregnancy. Nobody’s life is perfect. But God repeatedly uses women (and men) with mistakes and messy lives. The Bible isn’t just a bunch of good stories about good people doing good things—it’s the narrative of a sovereign and faithful God who loves human beings and stops at nothing to save us. He knows life is messed up so he never asks us to be perfect—he just asks us to love and trust him.

The names we choose show that our culture prefers for daughters to be beautiful mothers, not sinners draped in scandal and murder. But the Bible doesn’t let us view women so simply. The “bad” women can be faithful and the “good” women can be flawed. The Bible refuses to let us see women through the good/bad dichotomy our society has created. God loves both Sarah and Rahab, even if we don’t. Like Jacob, we desire the beautiful and not the ugly—but God chose to reunite humanity to himself through the descendents of Leah, not Rachel.

And whether we consider individual women’s stories to be exemplary or embarrassing, women throughout the Bible are changemakers who continually subvert manmade power structures. Jael goes against her husband’s loyalties, and Esther convinces a king to save her people during exile. Rahab allows the Israelites to destroy an entire city. Shiphrah and Puah and Miriam and Moses’ mother and Pharaoh's daughter form the unlikely team that saves an entire generation of Israelite babies and protects the child who eventually leads God’s people out of slavery. Sarah and Hannah and Rachel weren’t even supposed to be able to have children, but they do and their kids changed the course of human history. Ruth and Bathsheba become the mothers of kings in a family tree they shouldn’t have even been part of.

Biblical women repeatedly do the thing they “shouldn’t” do, but somehow the resulting chaos is always perfectly orchestrated for God’s plan for redemption. Biblical women make decisions that change kingdoms and dynasties and nations within moments, they turn the human world inside out—but God is never phased. He doesn’t need men’s empires and alliances. He doesn’t rely on human planning or effort. His ways are so much higher than our ways. God had absolute certainty in a plan that required centuries of situations that were impossible to predict and events that were never supposed to happen.

So yes, it is a woman who brings sin into the world. But it’s also a woman who carries the Redeemer into it and it’s a woman who first sees the risen Lord. Biblical women are far more complex, more powerful, more troubled and more admirable, than we give them credit for. So even if we don’t name our daughters after women like Rahab—their stories are proof of how incredible God is.

These statistics, and all other name statistics in this essay, are from the Social Security Administration.

Eva is more common, with 2562 Evas born in 2022. But my point stands—it seems that we’re slightly uncomfortable with girls named Eve.

my own parents made this choice too

By far one of my favorite pieces you’ve ever written! I love that you took the time to give attention to the complex and turbulent nuances of women in Scripture — and the implications of how we view them.