Riverbanking (Introduction)

"Wilmington is what happens when corporations control a city."

This post is adapted from the introductory chapter to my thesis, written in 2023 but still on my mind. If you would like to read the whole small-book-sized thing, let me know and I can send you a link.

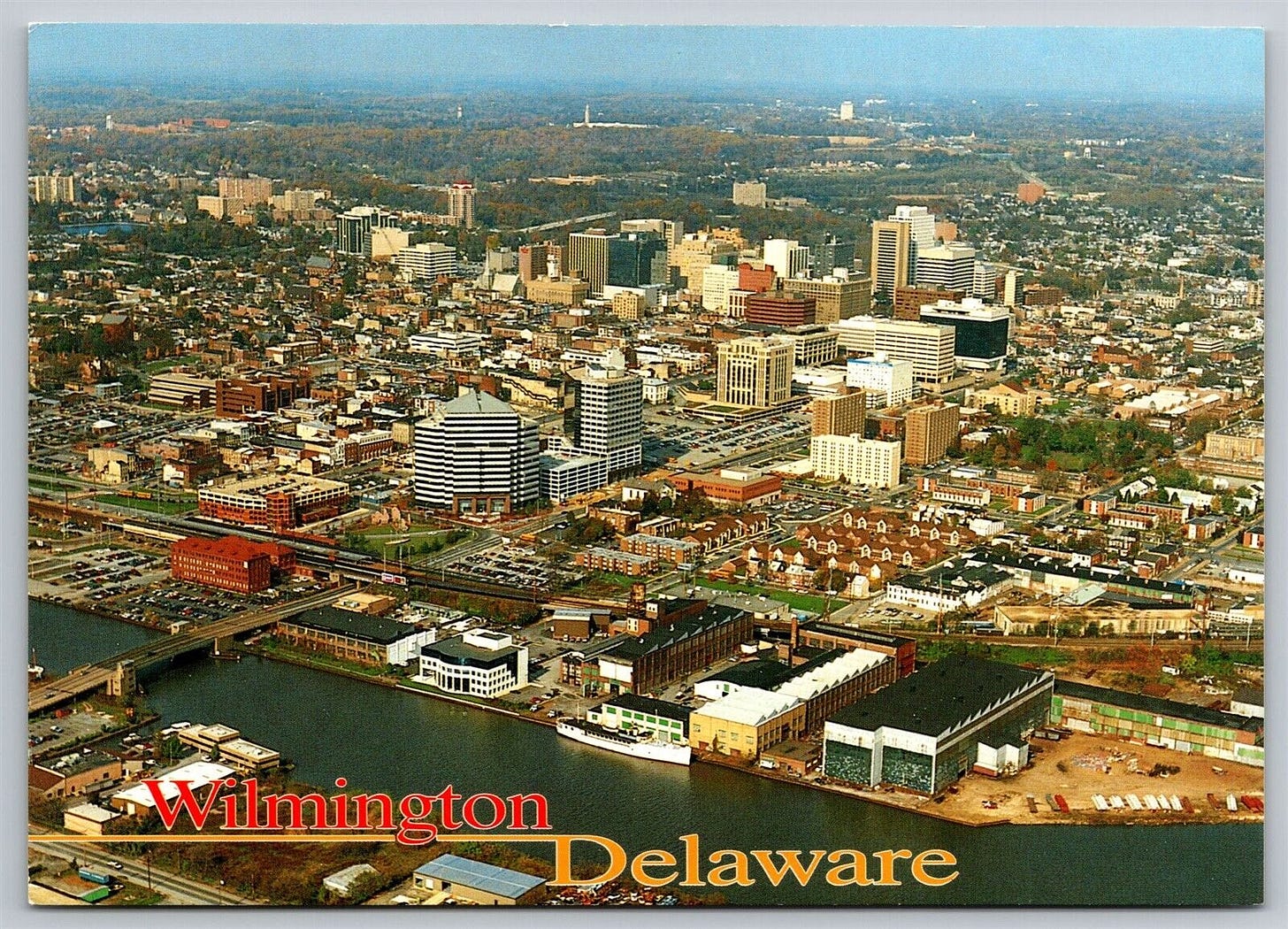

When I was sixteen years old I joined my high school’s crew team. Every afternoon during the spring of 2018 we drove downtown, lowered boats onto the water, and rowed a cross-section through the city of Wilmington, Delaware.

We pushed off from the dock and rowed east, past thousands of meters of rotting warehouses and sinking docks. We rested when we reached the I-495 bridge, where traffic thundered a hundred feet above our heads. As we caught our breath and massaged our calloused hands I stared ahead to the place where the Christina River meets the Atlantic. Massive cargo ships hulked in the fog beyond us, carrying bananas for the entire east coast.

And then the coxswain would call for the ports to back and starboards to row, spinning the boat around so we could row westward—away from the ocean and towards the heart of the city.

Starboard side, warehouses with shattered windows suddenly gave way to the railroad station and trendy restaurants that defined downtown. Beyond them, banks and office buildings formed Wilmington’s humble skyline.

Portside, we passed a small cluster of brand-new houses and a high-rise apartment building that still looked more like rendering than reality amidst the flat ecosystem of industrial wasteland and the Salvation Army. We rowed past the cranes that built warships and the luxury hotels behind them, passing under rusted railroad bridges until we reached the marsh.

***

The water itself was almost mythical. The Christina River was dangerously toxic from a century of pollution from the Du Pont chemical company and industries that disappeared long ago.

“Don’t swim in the river where the fish have feet,” one of my teammates once warned, echoing an aunt who worked for DuPont.

Of course, even if the fish were mutated enough to grow feet, just being able to maintain aquatic life was an improvement for the Christina.

On one hand, it seemed like Wilmington was an aging, emptying industrial town, a place of poverty and pollution, the shell of a tiny city that had been abandoned. Almost 20% of the office space was vacant. In 2018, 38.5% of the children in the city were living in poverty, and many of them would stay there. That same year, Wilmington was designated as one of the hardest places to “achieve the American dream.”

But, clearly, there was also something bright and bold and brand-new injected into this city. Someone was building hotels and apartment buildings along this river. There were boathouses for high school crew teams like mine. There was an invisible force that transformed some parts of the city while ignoring the rest.

I can remember falling out of sync with the rest of my boat, losing myself in the hotels and warehouses and rowing at my own distracted pace. My coach told me to keep my eyes in the boat — but I couldn’t help staring at the city. I just had so many questions.

***

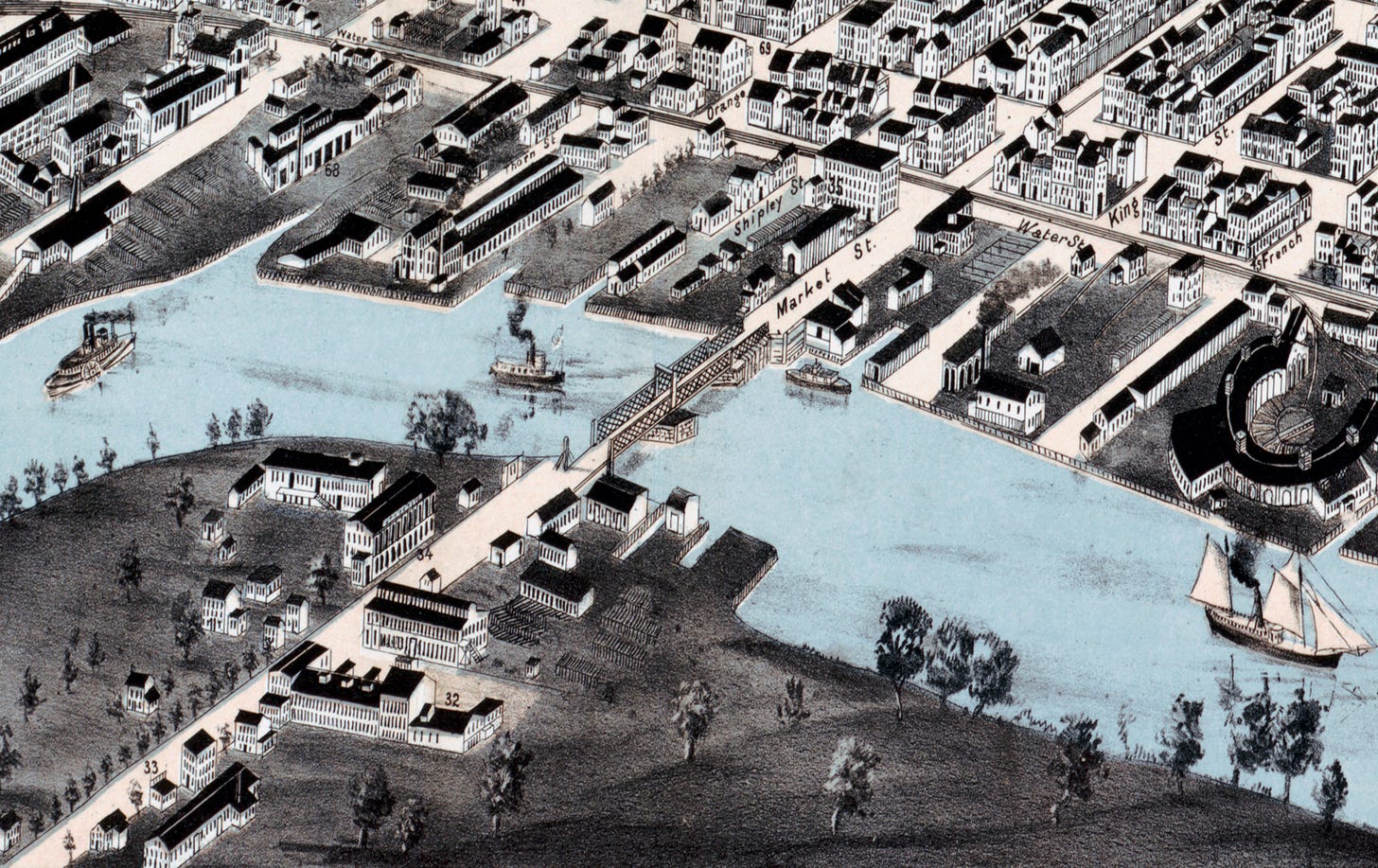

After the Civil War, Wilmington was a thriving industrial city. It was home to the DuPont chemical company, as well as other manufacturers along the Christina River. But in 1899, Delaware turned corporate law inside out by giving corporations all powers not restricted by law—leading companies to reincorporate in Delaware and boost the state’s tax base. In 1918, Wilmington was the wealthiest city per capita in the United States.

After WWII, Wilmington faced deindustrialization, white flight, and suburbanization. Delaware’s solution to the social and economic crises of the 1960’s was to write even more attractive corporate laws, giving businesses unprecedented freedoms. This was only exaggerated in the 1980s, when Delaware passed the Financial Center Development Act, which deregulated credit card banking in hopes of bringing the financial industry to Wilmington. Even though Delaware’s tax base exploded, the cost of living increased and the service sector replaced manufacturing jobs — making life just as hard for the city’s poorest residents.

This is why I was used to rowing past homeless people, sleeping in the shadows of luxury apartments and bank headquarters.

In the 1980s, Delaware gave corporations the power to use their agent’s address to incorporate in the state—giving companies the freedom to take advantage of Delaware’s tax laws, without physically relocating to Delaware. So although Wilmington has a population of 70,655, there are 285,000 companies claiming 1209 N. Orange Street—a rundown little building only a few blocks from the boathouse—as their legal address. Downtown Wilmington doesn’t even have a public high school, but it (allegedly) has Apple, Bank of America, Coca-Cola, Ford, General Electric, Google, JPMorgan Chase, and Wal-Mart. And because it’s so easy to incorporate in the state, Delaware “companies” have been used to hire assassins, sponsor terrorists, pay hush-money, and cheat millions of people.

This thesis argues that legally and architecturally, Wilmington empowers businesses over its own people. The city is built on the expectation that a friendly business climate will produce a thriving economy. The social inequality in Wilmington is evidence, however, that a state governed by corporations rather than citizens actually enables an increasingly intangible, abstract, and exploitative economy, with no investment in the city’s land or residents.

In this thesis, chapters alternate between building analysis and historical overview. The building analysis chapters anchor this thesis to specific sites in the city ( the DuPont Building, Hercules Plaza, and the MBNA complex) as episodes in Wilmington’s relationship with its businesses. The historical overview chapters flow between the building analysis chapters, contextualizing the broader social, environmental, political, and economic situations that surround each building. By contrasting these two types of chapters, I hope to prove that a city is both a physical and abstract concept, and the attitudes behind political decisions also manifest in priorities for urban planning.

***

Over the centuries, Wilmington’s experiential and intangible realities have grown further apart. Businesses have dissociated from the landscape, abandoning the city. Wilmington still claims a place in the flow of global capital by becoming a tax haven and legal loophole, but has sold its statehood and floated away from its physical reality. Today the city’s government is a corporate dream and the river is a toxic mirage. Wilmington is a train-station city, a vehicle for wealth on its way somewhere else.

Throughout the process of writing this thesis, I’ve wondered how to redeem the place I love. It’s easy to read sensational facts about Delaware and feel that living there is akin to skimming across the surface of a sea of infinite and unknowable sins.

But Wilmington is not a uniquely corrupt city governed by especially nefarious people. Instead, it’s the truest representation of an economic system that prioritizes people over profits. Wilmington is perhaps the most honest city in America, because it is the place where the intangible forces that shape our world are made physical.

To stand across the street from 1209 North Orange Street is to stand face-to-face with financial deregulation, and be underwhelmed. To walk the desolate sidewalks surrounding the MBNA complex on a windswept December morning is to confront the consequences of corporate mergers. To drive through Wilmington is to understand the cost of neoliberalism, and ask whether it was really worth it.

Wilmington is what happens when corporations control a city. And the more I come to understand Wilmington’s history, the more I realize that much of this narrative is the story of every other city in our globalized, capitalist society. From Detroit to Dubai, Wilmington explains the world.