do you even live, bro?

On Wall-E, Orange Theory, Chloe Ting, FitBits, and the dangers of a touch-screen self

Watching Wall-E, released in 2008, was one of the more traumatic and existential moments of my childhood. It was the first movie I watched in a theater, and I still remember leaving the dark theater and walking into the parking lot, squinting in the sunlight and shaken to my core.

Trash is one of my long-standing research interests so I anticipate exploring this topic more in the future—but for now, suffice to say, there’s something about that, windswept, long-forgotten, literal wasteland where the movie begins that still haunts me.

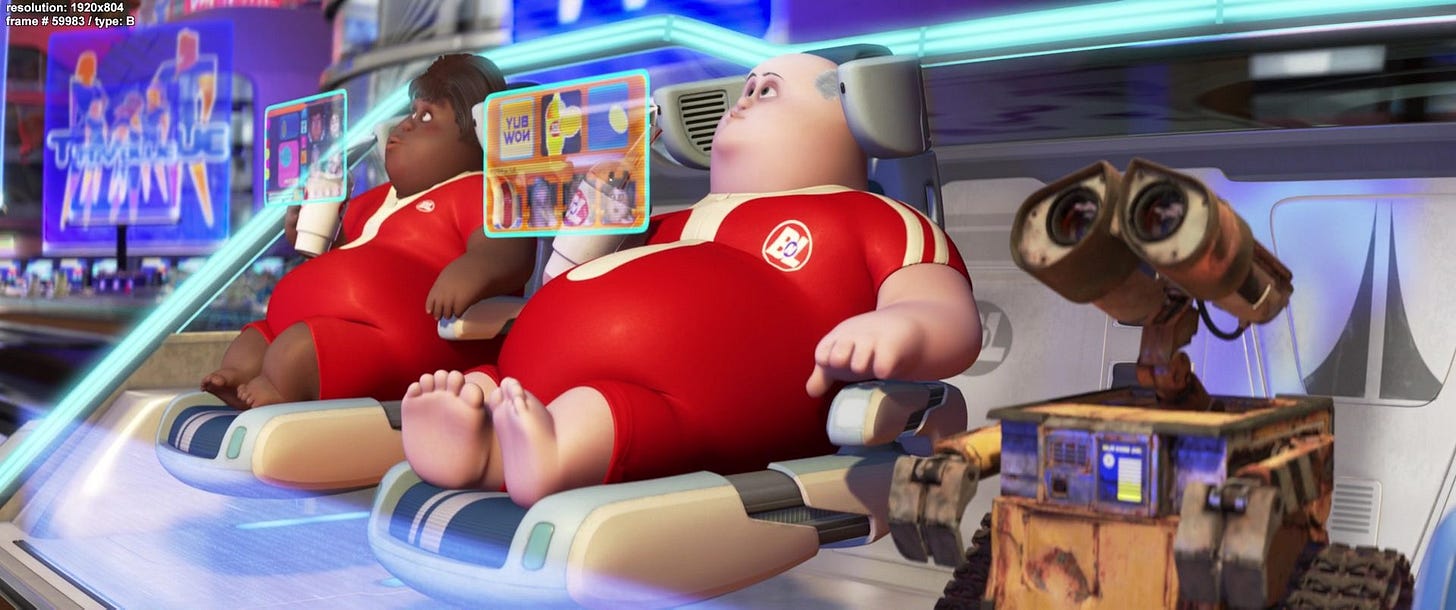

I’ve forgotten the plot to Wall-E, and the movie freaked me out too much to ever want to watch it again, but the other thing that sticks with me is the film’s prediction of a future humanity. We regress into aimless blobs of human beings, trapped between chairs and screens, only concerned with pleasure and completely helpless. We have the body composition of newborns, and are unable to function without screens.

It’s not hard to see echoes of this in our current reality. We’re already dependent on screens and immediate gratification. We’re the generation of tiktok, drive-thrus, netflix and Amazon Prime. We have access to more fat, sugar, and YouTube videos than we could ever hope to consume.

Right?

But I’d argue that the threat Wall-E really presents is a future where technology and the body have merged, and that future is already our reality—but it looks like health. Technology already mediates the relationship between our minds and our bodies. We’re becoming cyborgs with six packs.

When I’m in Delaware I work out at the YMCA, where the treadmill screen plays a continuous loop moving through a city or a beach from the perspective of a runner. It’s nice to glide through Abu Dhabi instead of staring at the missing right boob on the Hooters sign across the street—but sometimes I think, why don’t I run outside? Why do I have to drive to the gym to do something I used to do right outside my house? Why don’t I unplug and go run in the real world?

The answer is, I’d rather have control than freedom. I like running at 68 degrees or 4% incline or 5.6 miles per hour. It's so much easier to spend 21 minutes with my airpods in, letting Coach Bennet from the Nike Training App tell me how to breathe and how to run and what to think.

Today, even the most basic cardio machines give the exerciser statistics like their heart rate, speed, or calories burned. In his iconic essay, “Against Exercise,” Mark Greif writes that “Modern exercise makes you acknowledge the machine operating inside yourself.” Technology has revolutionized both our work and our workouts such that we’re no longer squatting and lifting and running and rowing to feed our families or build our shelters or travel somewhere else. We’re doing those actions with no context or purpose beyond ourselves. Attaching numbers to those actions makes it all the more clear that we’re not living, we’re trying to be productive and efficient—as if we’re looking at the profits for next quarter, not our own heart beats.

At OrangeTheory, heart rate monitors give participants “splat points” for every minute they spend in the fat-burning zone. The intrinsic motivation to work hard is replaced by the public display of how much fat you’re burning in comparison to everyone else at the gym—which is maybe just analogous to many people’s overall goal: looking hot, because you burned more fat than everyone else.

I’ve never personally done OrangeTheory, this is based on what other people have told me, so feel free to challenge or nuance my understanding—but I’m sure many of us can imagine our own evidence that much of our attitude towards fitness isn’t about nurturing and strengthening our bodies: it’s about carving them, reshaping them, stripping them down and building them back up. And when numbers—whether it’s miles or minutes, weight lost or lifted or gained—become our primary objective, our bodies are just objects to be manipulated to meet outside standards. We’re hardware to be optimized.

Every once in a while, when I’m especially tired, I don’t rerack my weights: I leave it for one of the men spending his thirties on growing biceps instead of children. I say that I do it out of respect for chickens, because his body is the product of a lot of bland chicken breasts, and if I don’t give him the opportunity to help someone those chickens would have lived and died their short, feathery little lives just for a man’s vanity.

But the global supply chain that brought chicken breast to his table is the same infrastructure that brings us sneakers and iPhones. The economy and technology that built his body are the same forces that build bridges. The body dependent on modern technology isn’t the obese people in Wall-E—it’s the physique that isn’t possible without protein powders and creatine supplements and a bench press. You wouldn’t get that body from hunting deer or plowing fields or herding sheep. The bodies that we idolize aren’t the result of the work our bodies were made to do—they’re the product of a constructed ideal.

We see this play out in an especially sad way with fitness influencers like Chloe Ting. For women, exercise isn’t marketed as a way to grow and strengthen yourself, to become someone who can live longer and run farther and play harder—exercise is sold as a way to upgrade your body, to achieve tangible results like a bigger butt or flatter abs or whatever the latest trend is. The body is treated like an iPhone that gets bigger or smaller with each new release.

Ultimately, I think this is the real danger of our hyper-technological fitness culture: it creates a digitized, touch screen self.

I recently borrowed my sister’s Fitbit, and found it both fun and horrifying that I could run diagnostics on myself, that I could read my body on an app. I could check myself the way I check the news or the weather. I learned that I have a resting heart rate of 53, and I come nowhere close to 10,000 steps a day. What I really liked was that the Fitbit gave me numbers that kept me accountable to myself—like working out five times a week, getting 22 “zone minutes” a day, or being active every hour. I liked being able to double tap my wrist, and objectively know whether I needed a snack or a workout or a walk or just to go to sleep.

But I shouldn’t need a Fitbit to know those things. After a week with a Fitbit, the first thing I would do upon waking up would be to open my phone and check my sleep score—as if the reward for sleeping was a number on an app, rather than waking up and feeling well rested. I don’t need an app to tell me if I slept enough—I can feel it. Technology offers to replace your body’s cues, rather than forcing you to listen to yourself.

The Fitbit was supposed to be waterproof, but it died every time I went swimming and one morning it stopped working all together. And despite all my luddite sentiments—I kinda wanna buy a new one.

Tools like Fitbit do help us be healthier, but they don’t solve the core issue: we’re more motivated by the feeling of instant accomplishment that apps can offer than we are by the quiet satisfaction of a healthy body. We don’t really care about investing in ourselves, we just want results.

And why do we expect technology to help us take care of ourselves anyway? You spend so much time in front of the big screen, you have to buy a little screen to tell you to go take a walk. It’s modern technology that abuses the animal of our bodies and dissociates us from our circadian rhythms and natural desires. It’s the privileges of modern life that give you the opportunity to stay up too late and sit at your desk too long and go through the drive-thru too much.

My real concern is that objectifying our bodies steals the realness and spontaneity of our lives.

The point of your body isn’t to be “perfect” by an arbitrary aesthetic standard. It isn’t to be “healthy” just for the sake of health. The point of a body is to love the world and enjoy it. The point of a body is to fully experience what it means to be alive. The point of exercising is to give yourself the opportunity to enjoy as much of life as you can, as long as you can.

Help your mom move furniture. Play tag with the little kids. Eat ice cream. Wake up at sunrise. Dance until dawn. Drink wine and swim in the Mediterranean.

Well maybe don’t do that, but – you get my drift.

this hit so hard (i say as i read this on my tiny screen) but i honestly really appreciate this piece! when everything around me is screaming one thing, being reminded of the truth in a few really well-written paragraphs means a lot!

finding out I can comment on a substack post, YOUR substack post is a life-changer🤩,, I am also terrified of Wall-E and equally terrified of objectifying ourselves in the name of aesthetics/productivity. such a good piece. i loved your heart for chickens :p