Cheer Captains, Sexy Babies, and the Monsters on the Bleachers

Taylor Swift’s musical career, my childhood trauma and lifelong insecurities, and how to love yourself

It’s 2009 in Southern Texas and I’m eight years old and I show up to summer camp with mismatched clothes and unbrushed hair, a homeschooled daydreamer too attention-deficit to focus on any sport except swimming.

And I have no clue who Taylor Swift is.

Fearless has just come out, introducing Taylor Swift to the American mainstream. All the other girls in my cabin are screaming the lyrics to songs like “Love Story” and “You Belong With Me,” which are at the top of the Billboard Hot 100.

I’m trying to pretend I know the lyrics, but I haven’t heard any of these songs before. I haven’t seen High School Musical, or a single episode of Hannah Montana, or the inside of a Justice.

My family doesn’t have cable, we listen to CDs instead of the radio, and I’ve never used a computer for anything other than Microsoft Word 2003 and Webkinz. I’ve seen more raccoons than tabloids. We live in a rural community where this is normal, so it isn’t until summer camp that I realize there’s an entire other world, where girls do cheerleading and wear trendy clothes and watch television.

Taylor Swift symbolized the line that divided my world from theirs. And kids can be cruel, so the other girls taught me that not knowing who Taylor Swift was—and thus everything associated with being a weird, sheltered, unstylish kid—was something to be ashamed of.

I grew up with a complicated relationship with Taylor Swift. On one hand, I felt that she represented a self-centered mindset that was completely oblivious to other people. The girls screaming “she wears high heels/I wear sneakers” were the ones who told me that my sneakers were boys’ shoes. Literal cheerleaders sang “she’s cheer captain/I’m on the bleachers,” and then made fun of me for being bad at basketball.

The irony is that “You Belong With Me” is the essential I’m-not-like-the-other-girls song, but it belonged to the ingroup. Wearing t-shirts and living in a community full of cheerleaders is just being a normal human while living in the South. Adopting an I’m-not-like-the-other-girls attitude implies that you see yourself as unique for being a three-dimensional person with desires—which means that you don’t see other people as equally real human beings.

Throughout Fearless, Swift paints herself as the underdog, but her songs—particularly with their country flair—portray an aggressively white, middle-class, conventional, American Dream life. Taylor is the ultimate cheer captain—so for her to claim that “I’m on the bleachers” entirely erases all the girls who are actually on the sidelines of society.

But summer camp didn’t teach me to hate Taylor Swift; it taught me to hate myself. As much as I resented Taylor Swift, I so deeply wanted to be accepted into her world. I wanted that high school fairytale romance. Taylor Swift was for pretty Texas girls with iPods and cute outfits and secret boyfriends, not the girls with overprotective moms and an obsession with the Trojan War. Taylor Swift was for girls who are funny and popular and beautiful. Girls who belonged.

And I wanted to be one of them.

Years later, my family moved to the East Coast and I had internet and the first thing I listened to was Red. I replayed “I Knew You Were Trouble” and “22” and “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” until I knew the lyrics—not because I actually liked the music, but just so that I’d never have to be the only girl who doesn’t know who Taylor Swift is.

By 2012 Taylor Swift had a smoother, more mainstream pop music sound. Her songs from this era are about messy relationships and heartbreak—but she’s never at fault, and maybe even enjoys the dysfunction.

She sings “the blame is on me,” but only “'cause I knew you were trouble when you walked in.” She can be hurt, but she’s never in the wrong. She claims, “we are never ever ever getting back together,” but the upbeat, repetitive chorus suggests that this is just another temporary breakup, and it’s totally not toxic—it’s actually fun! These are cheer captain problems. Having boy drama is part of being a girl who belongs.

I left homeschooling for a public high school in 2015. I don’t think I even knew anyone who had attended a “real” high school. But I imagined wearing the same khaki pants and polo shirt as all the other girls and being “normal.”

But I lacked a Vera Bradley lunch bag, an iPhone, shorts several inches above dress code, and the chutzpah to get away with wearing them. I was still a summer camper with boys’ shoes.

I did find myself sitting around lunch tables with new friends, but still fell silent when they reminisced about High School Musical and Spongebob and all those childhood memories I didn’t share. Deep down I was still the girl who didn’t know who Taylor Swift was.

1989 was released a year earlier, and still played on the school bus radio. I liked “Wildest Dreams” and “Welcome To New York.”

But “Bad Blood” and “Shake It Off” just annoyed me. “Bad Blood” blames someone else for a failed relationship, telling them “so take a look what you've done.” And while I don’t deny that Taylor has been betrayed, exploited, and snubbed throughout her career, as a highschool freshman it was clear to me that she was still the same oblivious, Fearless Taylor I met at summer camp. She still refused to be accountable for how her actions affected other people, and excluded the possibility that she has ever been anything but the victim.

And, clearly, Taylor Swift does everything except “Shake It Off” when people hurt her. She’s addicted to the pain of broken relationships, and just keeps leaving a “Blank Space.” She cares so, so much about being loved—and she would rather glorify cheer captain problems than face her insecurities.

As someone who had been hurt by Taylor Swift, and wanted the clout that came with cheer captain problems, I didn’t have much sympathy for her.

In 2019, I graduated from high school—homecoming princess, varsity swim team, heading to Yale as a Classics major—still weird, but having spent ten years compensating for it.

Reputation was still on the radio, and Taylor was beginning to release singles from Lover.

I’m not going to dwell on “You Need to Calm Down” or “Look What You Made Me Do.” The tiles speak for themselves. “ME!” annoys me too much to even listen to it again so I could write about it, and frankly I don’t understand how two widely respected songwriters could produce such an embarrassment of a song.

By 2019, Taylor’s top hits blamed unspecified enemies while maintaining the claim that she’s a rational, innocent, decent human being. You need to calm down. Look what you made me do.

It’s a framework I recognized from Red and 1989 – Taylor presenting herself as powerful, impeccable, untouchable. She’s the “actress starring in your bad dreams,” she’s smarter and harder—but if she’s a sinner, it’s only because she’s a victim.

What bothered me so much about Lover is that Taylor’s mask had grown insultingly shallow. Empty assertions like “you’ll never find another like me” only emphasize her obsession with her own reputation. Taylor Swift was only a metaphor away from desperate loneliness and thought a pink album cover would convince us she was a resilient superstar, not a woman in crisis.

The internet classifies many of her songs from this era as “Bubblegum Pop,” referring to a catchy genre meant to appeal to children and adolescents—but I think bubblegum is also a perfect metaphor for the lyrical content of these songs. It’s bright and sweet and big, but crushed so easily. There’s nothing behind that inflated facade.

I moved into my college dorm at Yale in August of 2019, a week after Lover came out. I spent the summer curating Pinterest boards of dorm room ideas and outfit inspiration and everything I needed to look and act like a College Girl. I was going to fit in this time.

But my roommate was literally Taylor Swift.

Perfect body, perfect hair, wearing a reputation t-shirt. Her dad was a lawyer who graduated from Yale. I think she mentioned that her mom was a model. She went to boarding school. She was eight inches taller than me and a year older. She had lived away from home longer than I had been in the American education system. She knew how Yale worked. She belonged there. She was everything I had ever wanted to be, every girl who had ever made me feel like I wasn’t enough.

I was an outcast summer camper.

We got dinner together on the first night, but we barely spoke for the rest of the year. She slept at her boyfriend’s place (he was a sophomore on the heavyweight crew team) so I only saw her when we were both at the gym.

She was happy—and couldn’t care less about me. I just didn't exist to her. She went to regattas not football games so I wasn’t even on the bleachers.

I had spent ten years resenting the Taylor Swifts of the world while also trying to become one of them—and I failed. I had coveted Justice and Lily Pulitzer and Lululemon and finally I was standing in our dorm room staring at a crumpled Canada Goose jacket, realizing, I will never be enough for Taylor Swift. And if this is who she is, I don’t think I want to be.

COVID-19 cut our first year short, and we never spoke again. Taylor Swift (the real one) released folklore and then evermore, and I didn’t even bother to listen. I lived with Taylor Swift, and she didn’t even show me basic respect. If I was the girl who didn’t know who Taylor Swift was, that was fine. I didn’t really care about her problems anymore.

I didn’t plan on listening to Midnights when it was released in October 2022. But a friend texted me a link to “Anti-Hero” and that one song changed everything. I popped in my earbuds on the way to swim practice, and had barely taken ten steps before I had to stop on the sidewalk and read the lyrics.

From the first lines, Taylor admits that she “gets older but just never wiser,” repeatedly making the same mistakes. She’s depressed. She’s ghosted people. Her actions result in “prices and vices,” she “end[s] up in crisis.”

Taylor Swift finally confessed that she will “look directly at the sun but never in the mirror,” taking on the world before acknowledging her own shortcomings. She “wake[s] up screaming from dreaming/One day I’ll watch as you’re leaving,” because she’s insecure and abandonment is her greatest fear.

For years, I had felt like Taylor Swift saw herself as totally innocent despite all the carnage left in her path. She was the symbol of my deepest wound—and she was happy, perfect, beautiful. She was the first reason I hated myself, and everyone loved her.

What’s more isolating than that?

But in Midnights, I saw Taylor unfolding her own life with sober, moonlit clarity and acknowledging that she is destroying herself. She let go of that bubble gum facade and walked through the ruins of her own trauma.

This is what I had needed for a decade. I needed Taylor Swift to confess that her universe was crumbling and that even cheer captains face consequences. I needed her—on behalf of all the girls who had hurt me, from summer camp to college—to acknowledge that she was broken, too. I needed her to admit that her life wasn’t a fairytale. She is the anti-hero. She is the problem.

“Anti-Hero” softened me, but “Mean” taught me to forgive. In “Mean” Taylor still has her southern twang as she sings along to acoustic guitar about a man who told her she was nothing. And as she tells him that he’ll someday be living a dead-end life while she’s ruling the world—my heart hurts because I realize that through every stage, every song, Taylor is still a girl trying to prove she can sing.

“Someday I’ll be living in a big old city,” she promises him, and I wonder whether the electric joy of “Welcome to New York” is really a country girl saying look, I made it, with the hollow pride of someone who has no clue how cold the city can be.

“Someday I’ll be big enough that you can’t hurt me,” she says. But twelve years later Taylor Swift is huge, and she will realize that she’s not a sexy baby, both innocent and desirable—she has become “the monster lurching towards your favorite city,” ready to destroy all you love and leaving chaos in her wake.

No matter how successful she appears, Taylor will never feel like enough.

But I’m the same way. No matter what anyone tells me, I’m still trying to prove that I belong to society just as much as girls who watched Disney channel and wore peace signs and sequins. I’m still just a kid in Texas who doesn’t know what’s happening but wants to be part of that big, glamorous world where everyone is listening to Fearless. Ultimately, Taylor Swift and I are both hurt little girls. And now we’re both women in a big city trying to find our place in the world.

I can’t hate her anymore.

Growing up, I was frustrated with Taylor Swift because no one was more popular, more praised, or a more perfect example of beauty standards than she was—and yet she was completely focused on her insecurities. She was the most loved woman in America, but an entire nation’s opinion meant nothing to her.

Now, I’m wondering how I could see that even Taylor struggled, and still imagine that I’d ever be satisfied with myself.

I’ve come to see that we assess women using the bleachers/cheer captain dichotomy. Either you’re pretty and popular—or you’re weird, ugly, outcast. We do everything in our power, from buying clothes to getting plastic surgery, to put ourselves on the “right” side of that dichotomy—a side that’s almost always thinner, blonder, richer, whiter, younger.

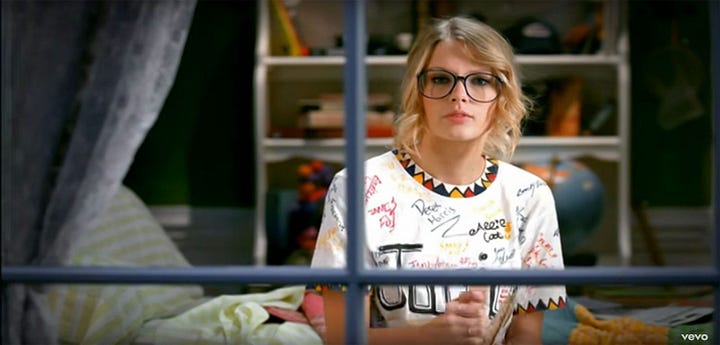

But the line between cheer captain and bleachers, between monster and sexy baby, is an illusion. In the music videos for both “You Belong With Me” and “Anti-Hero," Taylor Swift plays her own doppelgängers because in each song, the two characters are equal halves of the same person. Beneath the makeup, we share an identical struggle.

We all believe that “she’s cheer captain/and I’m on the bleachers,” because we make this distinction by comparing ourselves to an unattainable ideal—so even Taylor Swift comes up short. Maybe we thought the enemy was the other girl, but really we’re tormented by the made-up, glittery, popular versions of ourselves we thought we needed to become.

So if we don’t love the girls on the bleachers, we don’t truly love the cheer captains, either—because every cheer captain was once a girl who believed she had to get off the bleachers to be loved. If we don’t love the monsters, we don’t really love the sexy babies. If love is something that women have to earn, it isn’t really love. So whether society has defined you as desirable or not, you can only find freedom by rejecting this dichotomy and choosing the truth: you don’t need to be desired to be loved.

So I couldn’t love myself if I still resented Taylor Swift.

And I’ve seen Taylor Swift spend years trying to be loved, known, blameless, beautiful—but I wonder if the only way for girls like her to believe they are enough is to look at little girls like me, and believe that we are enough too.

The Taylor Swift piece I needed!! Tying your own inner struggle with what the doppelgängers in the music videos reveal was *chefs kiss* ...do I like Taylor Swift now??!!🤔😩