message me if you would like the version with sources cited :)

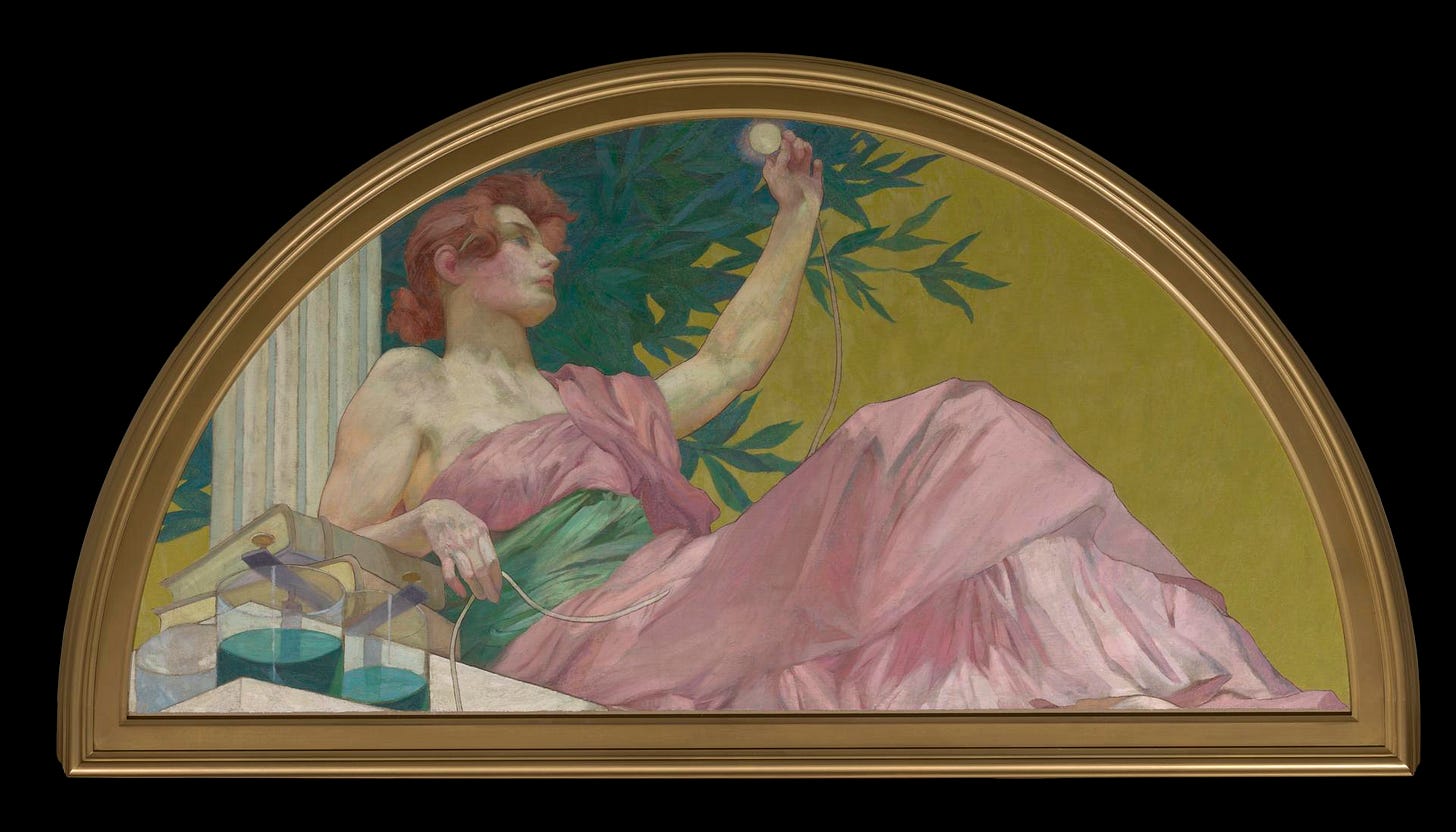

I first notice it when I’m trying to sketch the Muse of Electricity’s neck (1893). My twenty-first century hands and eyes, raised on Barbie dolls and Disney Princess movies and doodling cartoon girls, automatically draw a dainty little connection between her head and body. But this is grotesquely incorrect. Her neck is thick and strong. Regal. Unashamed of its job: holding up a perfectly symmetrical nine-pound head.

The sketching instructor tells us to move on to a new piece, and this time he asks us to sketch without looking at our work until we’re finished. So I begin sketching Undine (1880): a marble sculpture of a mortal but soulless sea spirit character. When the instructor tells us that time is up and we can finally look down at our sketches, my stomach twists. I magnified her chest and warped her dainty waist, mentally photoshopping her already idealized body. I’ve awkwardly scribbled the fat over her stomach, because even though most women have that softness I’ve never drawn it before. Unconsciously I’ve corrected a master’s work, my brain interrupting the communication between my eyes and my hands to say, surely you’re mistaken—isn’t this what a woman should look like?

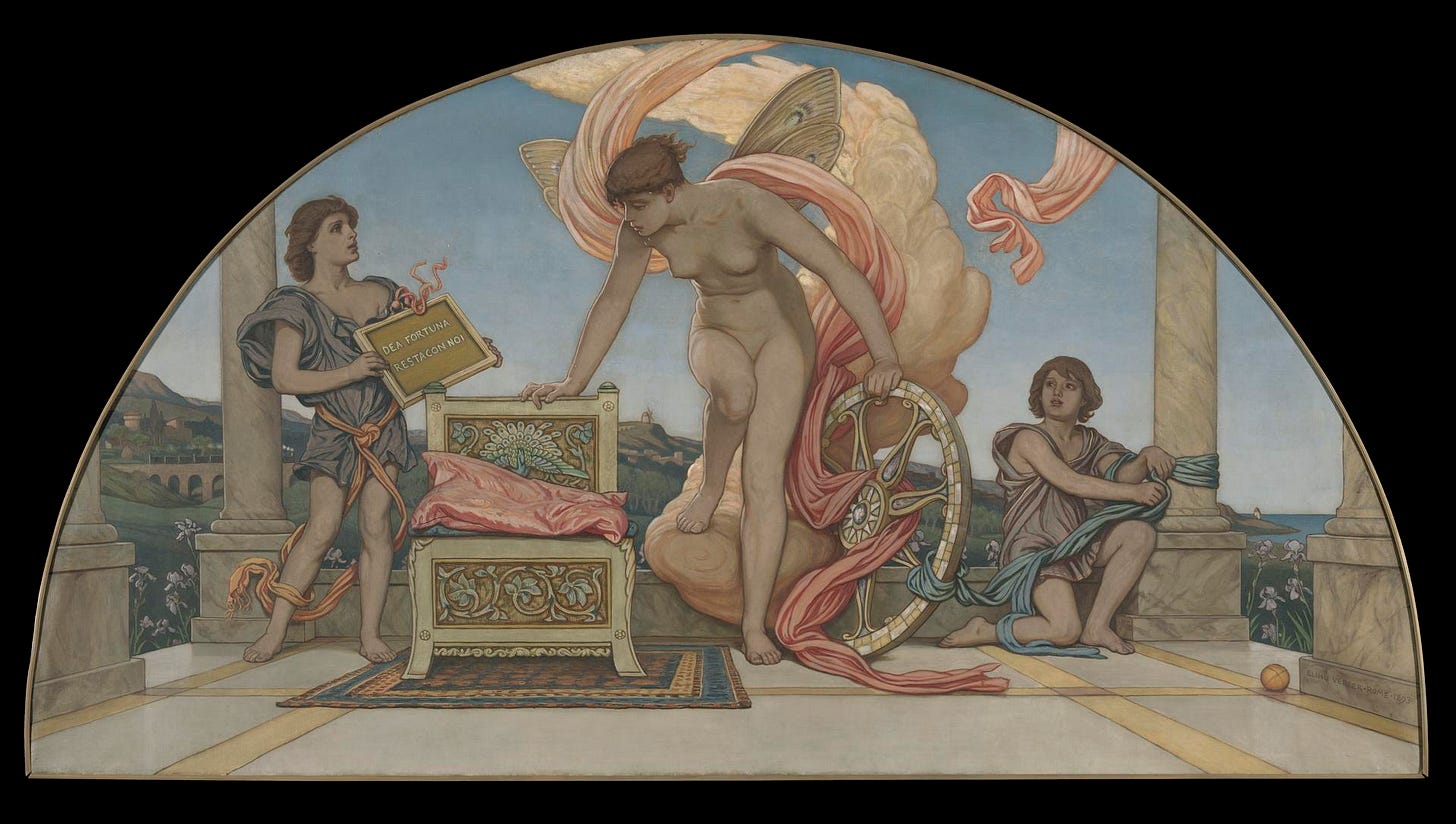

Again I’m sketching Goddess of Fortune Stay with Us (1893) and as I begin to trace the contour of her body I’m shocked that the loose curves I lay down for her arms are the same size as the soft angles of her chest. But as I work on the drawing further I realize that I’ve drawn her from a completely incorrect perspective. She’s taking up far more space than I thought she was and I shrunk her body to fit where I thought it should. I didn’t leave enough space for the folds and wrinkles of her stomach, the rich topography of a fleshy body.

I look around the gallery and I think, these women look so normal. They’re beautiful, undoubtedly, but not otherworldly. They look like women I’d see jogging in the park, or on the leg extension machine, or wearing sneakers in the grocery store.

We pride ourselves on being an era where women can be strong, so why am I admiring the Muse of Electricity’s gains? We talk about body positivity, so why is an 1800s marble statue’s tummy familiar to me? The ladies who modeled for these paintings and sculptures couldn’t wear pants, couldn’t vote, couldn’t own property… So why do they look more normal than plenty of influencers? Why do they look more powerful than most runway models?

***

I was sketching on the second floor of the Yale University Art Gallery, in the American Art Before 1900 collection. These works all would have been displayed in private homes during the Victorian Era (~1837-1901), the Gilded Age (late 1870s to the late 1890s), and the beginning of the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s). And this was a time period where (some) women could become heroes.

Victorian society was preoccupied with virtue, and women used that ethos to argue for their own rights. For example, social regulations for upper- and middle-class families (called the “Cult of Domesticity”) prescribed that women were responsible for the physical and moral goodness of their own spheres: the home.

“Sure, women agreed, “we’re so weak and sensitive and emotional, we should use our natural gifts of child-raising and homemaking and just leave the mess of politics to the big burly manly men. We’ll stay home and raise pious children.”

“But,” they reasoned, “shouldn’t we be educated enough to raise smart kids? And if we’re the delicate moral compass of society, shouldn’t we have a say?” So women became leaders in social reform, starting organizations like the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Hull House. Although the women’s rights movement largely excluded Black women, many individual women were passionate abolitionists.

This logic extended to personal wellness. Shouldn’t a woman be healthy enough to fulfill her oh-so-important duties as a wife and mother? One female writer claimed that “woman was neither made a toy nor slave, but a help-meet to man,” giving her obligations “which cannot be met so long as she is the puny, sickly, aching, weakly, dying creature that we find her to be.” She isn’t arguing with her culture’s gender roles—just saying that women could be more feminine without the corsets and petticoats.

So nineteenth-century doctors and health reformers asserted that if women could breathe and even exercise, they would be better, healthier mothers. A culture that values goodness and wholeness and honesty and strength became a culture that valued healthy women and thus found beauty in a pure, natural, uncorseted body. So by the 1890s, images of women with rolls and muscles were perfectly acceptable home decor. An Undine seeking justice, a goddess of Fortune who blesses children but has places to be and things to do, a muse playing with electricity—these were acceptable female figures and their healthy, functional bodies were acceptable bodies.

***

But strength was admired as long as it was conceptual, not embodied. Goddesses can be jacked, but wives shouldn’t be. All three of the pieces I studied would have been displayed in the homes of the rich and powerful. Muse of Electricity and Goddess of Fortune Stay with Us were designed for panels above hallways and dining rooms—they’re meant to be literally unreachable, far above us, olympic ideals we admire but don’t interact with. And they’re strong. Undine, however, is a tangible, three-dimensional, approachable sculpture. And she isn't heroic. Her body is beautiful but perhaps not legendary. She’s romantic but not imposing.

Muse of Electricity was part of Henry Siddons Mowbray’s nine-panel series, Lunettes. And both the nine Lunettes and Goddess of Fortune Stay with Us were commissioned by Collis Hunginton, a railway tycoon, and his wife Arabella. And Collis Huntington knew a thing or two about power. Born in 1821, he grew up in poverty—but by 1890 he was president of the Southern Pacific-Central Pacific rail system: an enterprise many writers refer to as an empire. At his death in 1900, he had an estimated net worth of $35 million to $50 million, worth $900 million to $1.3 billion in today’s money.

One biography of Huntington calls him “a robber baron, the greatest railroad mogul of them all,” whose “highhanded practices” were “definitely outside the law, although well inside the prevailing morality of his time.” This was the era of Vanderbilts and Carnegies and cotton mills and monopolies. Coal and steel and steam trains and sweatshops and slums. Labor strikes and dynamite and gold spikes and coal mines. Grimy hands and inky newspapers, war in the Philippines; lightbulbs and Yosemite and the “Battle” of Wounded Knee. The Huntingtons lived in a sooty, sweaty, “separate but equal,” sepia-tinted America where yes, women did have the agency to fight against child labor—but only because there were still thousands of immigrant kids smoked and scarred in industrial factories.

Strength and power, no matter what the cost to others, was national policy, too. From Manifest Destiny to the Spanish-American War, the 1890s saw America become an imperial power asserting its own strength over other nations. All three of the pieces of art I’m thinking about are neoclassical, based on Greek and Roman characters and aesthetics—so regardless of what the actual figures look like, each piece is a reference to the grandeur of fallen empires. Displaying Undine or Goddess of Fortune or the nine Lunettes isn’t an endorsement of strong women—it’s a way of saying, we picked up where the Romans left off. We’re conquerors too.

***

But if money is power, there’s one woman in this story who is absolutely shredded: and it’s Arabella Huntington.

Like Collis, Arabella was born into poverty. She was probably a sex worker, and she probably never actually married her first “husband” — but the only certain detail about her early life is that she was Collis’s mistress for 14 years before his first wife died. So for the virtue-obsessed Victorian elite, Arabella was unforgivable. Despite her marriage to a railroad magnate, despite the fact that her mansion on Fifth Avenue was only a few blocks away from the Vanderbilts and the Astors, the families who ran New York society ostracized her.

When I first read about the millions of dollars she spent decorating and redecorating her home, commissioning artists to paint Lunettes and Fortune, I thought, rich people are insane. Now, I see that she was doing what anyone else would do: attempting to buy a place in a world that rejected her again and again.

When Collis died in 1900, Arabella Huntington became the richest woman in the country. She spent thousands of dollars on pearls, nightgowns, skincare, and European art. In portraits, she wears glasses—completely defying feminine beauty standards of her time. To me, her face says, I know I’m beautiful, but I don’t even have to care. I know the world is looking at me—but I’m looking right back.

Arabella Huntington— boss babe, richest woman in the country— spent a lot of money on her own dreams, desires, and deepest insecurities. But she also founded The Huntington Library in San Marino, California. She built a girls’ dormitory at the Tuskegee Institute. She helped fund the Hispanic Society of America. In 1901 she donated the equivalent of $3.6 million dollars to found a cancer research center which eventually became Sloan-Kettering Memorial Hospital.

Of course, gilded-age philanthropy is complicated. Does Carnegie Hall really justify harsh working conditions and injury or even death to the strikers who stood up to him? Does the Rockefeller Center justify crushing the independent oil industry through illegal practices that permanently redefined the limits of the American legal system? I don’t think it comes anywhere close.

But the 1890s understood something about power that our generation doesn’t: strength exists for others. If you’re a goddess, it’s so you can bless children. If you’re a muse, it’s so you can electrify and empower society. If you’re the wealthiest woman in the nation, it’s so you can share art and culture with the masses.

Today, “strong woman” means girl boss, boss babe, girl power power suits power walking in heels working your way to the corner office protecting your peace lifting as much as one of the guys padding your resume building your own empire… And I think we’re selling ourselves short. We think strength is the ability to take care of ourselves, but it’s actually the ability to love the world well. Regardless of gender, strength is the ability to bear a friend’s burdens. It’s carrying someone else’s bag and listening to someone else’s struggles and offering all the help you can. It’s tutoring kids and donating food and smiling at your barista and loving people you have no reason to care about.

So don’t show me your gains— show me what your community gains.